Expelling the enemies of nature: antimonial cups

In the 17th century, antimonial cups allowed sufferers to purge themselves - sometimes violently - of disease

Art sick and burnest with desire Thy lost health to renewe? At hand a medicine safe I am If putte to uses due.

Such poetical reassurance is no longer to be found in medicine package inserts, but the ailing person of 400 years ago might have found encouragement in these lines accompanying the purchase of an antimonial cup.1

The use of antimony in medicine dates back to antiquity, and fits within the persistent idea that the body can expel disease in the fluids that issue from it. I’ve written about leeches and mercurial salivation as two ways of doing that, but antimony operated by purging – its poisonous nature meant that anything in the digestive system would violently leave the body by the nearest exit. While this doesn’t sound like something anyone would intentionally inflict upon themselves, the notion of enduring short-term discomfort for a perceived cure does have its logic and remains necessary in many modern treatments.

In 17th-century Europe, the fashionable way of taking antimony was the antimonial cup – a small vessel moulded from a pewter that comprised tin and 7 – 15% antimony. Wine left to sit in it overnight would become impregnated with tartrate of antimony, a valued emetic.

In France, antimony was prohibited by Act of Parliament in 1566 due to its dangerous effects, and this might have influenced the development of the cup form. Sir StClair Thomson, writing in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine in 1925, suggested that antimonial cups were a way of getting round the ban – they were easily hidden at home and did not require regular efforts to get hold of the forbidden substance. The very fact that it was illegal might have boosted its popularity – as Sir StClair pointed out, ‘the banning of any man or his methods at once makes a hero of him, and a panacea of his nostrum.’2

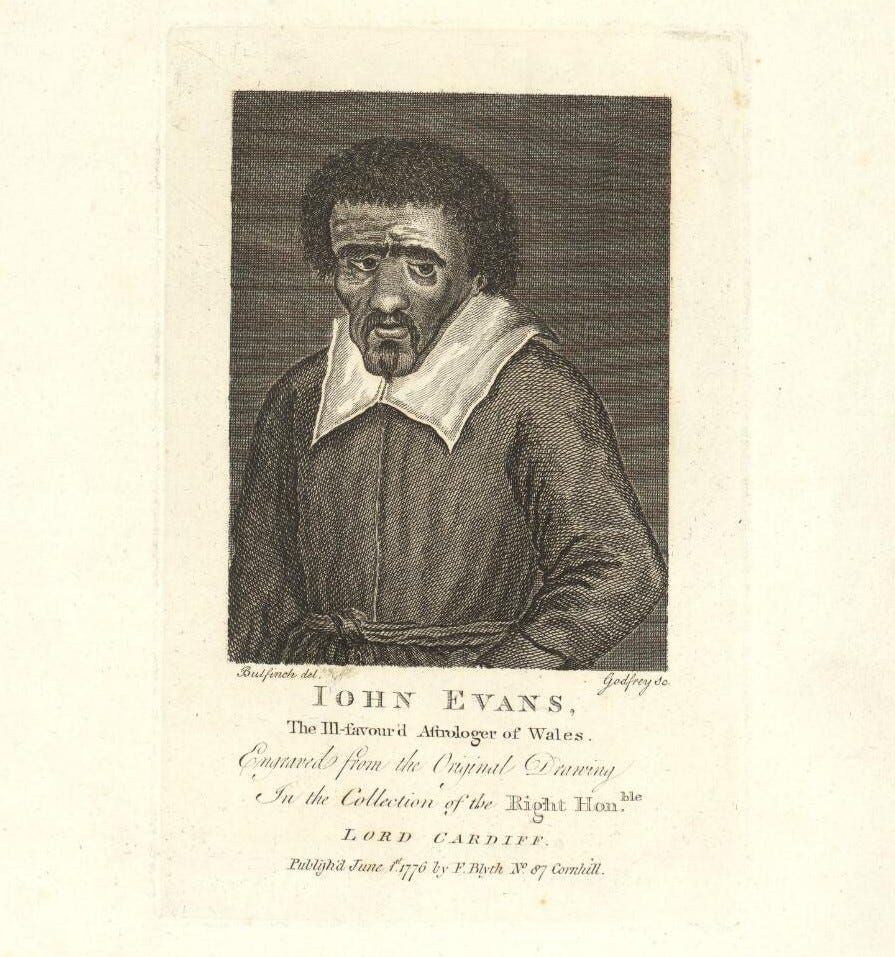

For the 17th-century Londoner, the place to obtain an antimonial cup was Gunpowder Alley near Shoe Lane, where a hard-drinking Church of England minister named John Evans sold them from a small shop.

Evans (c. 1594-1659) was originally from Llangelynin in North Wales and moved to England as a young man to study at Oxford.3 After taking Holy Orders, he obtained a curacy in Staffordshire but in due course he was ‘enforced to fly for some offences very scandalous, committed by him in these parts’ and headed to London, where he practised as an astrologer and magician as well as selling the antimonial cups. His astrology student William Lilly described him as: ‘much addicted to debauchery, and then very abusive and quarrelsome, seldom without a black eye, or one mischief or other’. The first time Lilly visited him, he was lying in bed with a hangover.4

In 1634, Evans published a pamphlet, The universall medicine: or The vertues of the antimoniall cup to promote his product. From this, we can see that the cup was indeed quite the panacea. It would perfectly cure syphilis, epilepsy, gout, ague, madness, wounds and ulcers, and would even preserve the user against all infectious and contagious diseases.

To use the cup, Evans advised putting it in a well-glazed earthen pot and pouring around it some claret, white wine or ale. It should be heated for an hour then left in a warm place for twelve hours, after which the patient could drink a cupful or more. People who were not ill could take it in Spring and Autumn to maintain their health, while for confirmed diseases:

‘…it should be taken as often as it worketh, for when it hath vanquished and expelled the enemies of Nature, and prevailed against all the impurities of the body, it is at peace with all that is pure and good, and then will it work no more, & thereby you may be well assured that you are perfect well.’ 5

In 1640, Dr James Primerose of Hull published a scathing response to this pamphlet, criticising Evans for promoting the cup as something new even though antimony had been used since antiquity, and dismissing his customers as ‘the people who are always eager in their pursuit after Novelties’.

Although Primerose admitted that antimony could be useful in correct doses for specific conditions, he described it as ‘malignant and deadly’ when used indiscriminately, and warned that ‘it doth not gently but mightily provoke vomit and stool.’ He noted that Evans’ instructions to immerse the cup in wine made the cup shape pointless – a blob of metal would have the same result. One of his main criticisms, however, was that Evans was making a lot of money from the huge markup: ‘…selling such a cheap medicine at so deare a rate, the right use whereof he doth neither teach the people, nor I think he himself knows.’6

Primerose wasn’t the only person disgruntled by Evans’ pamphlet. Evans had included information in support of antimony from the writings of high-profile physicians, including Théodore Turquet De Mayerne, who was not impressed at having his name used in advertising. He wrote to the President of the Royal College of Physicians of London, who sent a delegation to the Archbishop of Canterbury to let him know about the behaviour of an ordained minister. The Archbishop had Evans’ stocks of his book destroyed, and appointed someone to search out any further copies that might be extant. During proceedings, information emerged that three people had died as a result of using the antimonial cups.

Evans, however, continued selling them, with later editions of his pamphlet adding glowing testimonials from users and expanding the treatment’s repertoire to include plague and smallpox.

‘What the Lord hath sanctified,’ he wrote, ‘and communicated for the health and profit of many, ought not to be concealed for the envy and displeasure of a few.’7

HistMed Highlights

RADIO: Tune in to Best Medicine on BBC Radio 4 on 14 November, 6.30pm, to hear me talking about some strange inhalation devices from the past. Kiri Pritchard-McLean hosts this hilarious and uplifting panel show, which will also be available to catch up with on iPlayer.

TOUR: Explore the history of the Lakeshore Psychiatric Hospital in Toronto on this guided tour of the patient-built tunnels and 19th-century cottages. The tour takes in the new exhibition, Grace: One story of thousands. 14 November 2023, 3pm EST, free tickets.

TALK: Author Suzie Grogan presents Death, Disease and Dissection: The Working Life of the Surgeon Apothecary, tracing the day-to-day practice of the earliest GPs from the making of pills and mixing of potions to tooth-drawing and blood-letting. 23 November 2023, 6pm, The Old Operating Theatre, London, £15.

CELEBRATION and BOOK LAUNCH: There is a special evening reception to mark the 85th anniversary of Wales’ Temple of Peace and Health in Cardiff. Author Emma Snow launches her book 'The First NHS', about her great-grandfather's work with the Wales National Memorial Association for the Eradication of Tuberculosis. 23 November 2023, 7 - 9pm, free tickets.

Thanks so much for mentioning my talk Caroline. This blog is a wonderful resource.